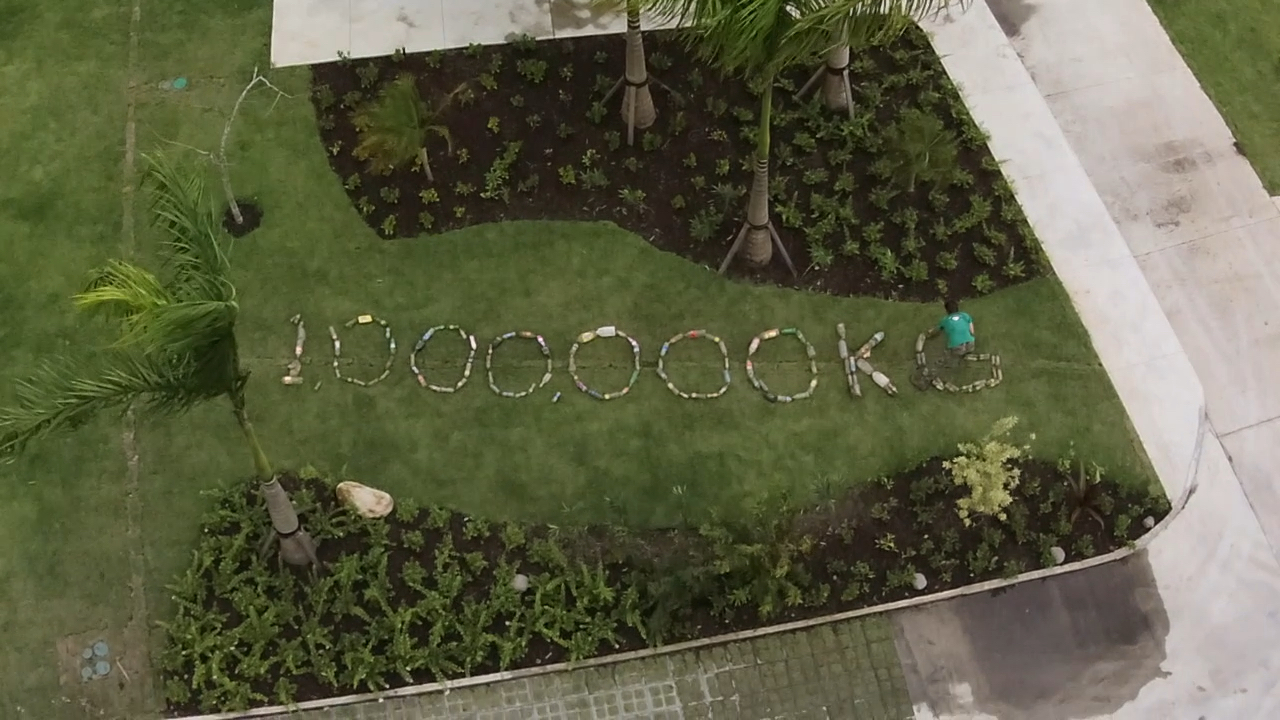

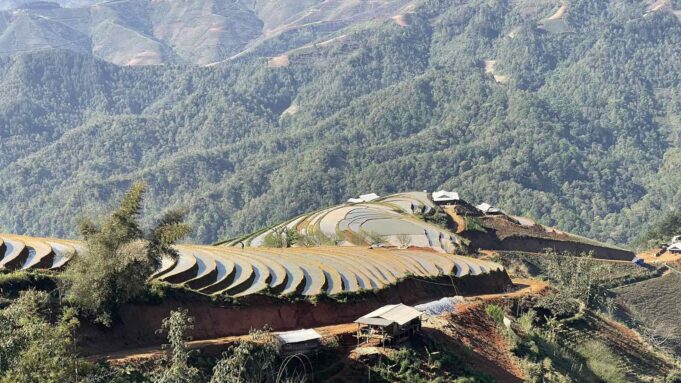

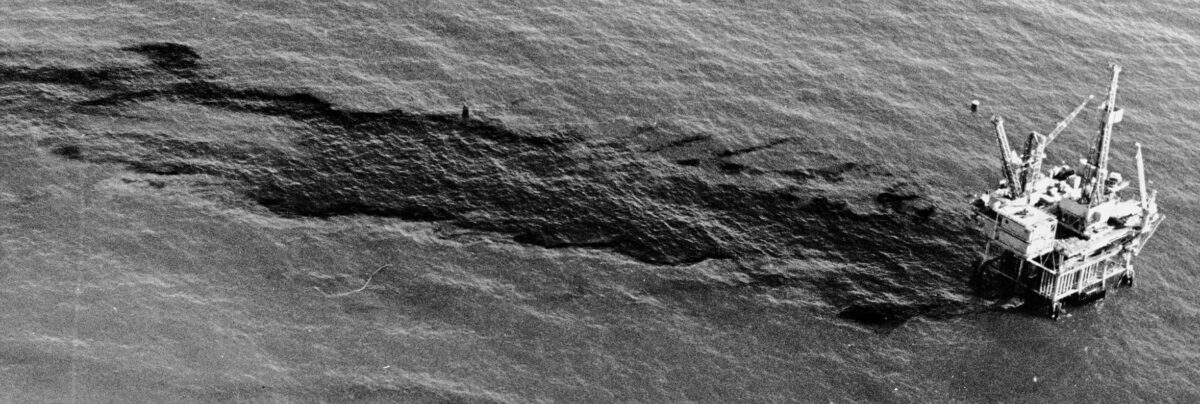

Since 2020, Ocean Conservancy has been working to reduce the amount of trash in the Song Hong, or Red River as it’s commonly called in English, and prevent it from reaching the ocean through a project called the Strategic Litter Abatement in the Song Hong (SPLASH).

Ocean Conservancy and our in-country partner, Centre for Marinelife Conservation and Community Development (MCD), have recently completed a public opinion survey in Nam Dinh, Vietnam, the city where the project is based. We sought to understand how SPLASH’s work to set up traps to capture plastic debris in the river and its associated communications campaign have influenced residents’ attitudes and perceptions of plastic waste. Before beginning the project, we conducted a similar survey and will compare the survey results to evaluate if there has been a measurable change.

Although we do not yet have the survey results, we do see evidence of broad community support of the SPLASH project in their interest in continuing the operation of these important trash-collecting devices – even after Ocean Conservancy’s involvement draws to a close. The Department of Natural Resources and Environment for Nam Dinh province have agreed to assume ownership and management responsibility for the trash traps starting in 2024. This commitment demonstrates that the local community and the decision makers see value in the project.

In fact, a key lesson learned from our project is the importance of regular interactions with political leaders on the national, municipal, and commune levels of government. The SPLASH project consists of five separate devices in five different locations, managed by five different communes, and thus, each required a separate set of permits at different levels. While the permitting process was lengthy and complex, it had the benefit of engaging with government officials. In addition, Ocean Conservancy and MCD had numerous meetings throughout the project to provide updates and share data and results. Building these trusted relationships and sharing knowledge facilitated the willingness of the local authorities to sustain the trash traps after the SPLASH project finishes.

One important design aspect of the traps is that the devices are simple and inexpensive to build, operate, repair, and maintain. When we decided to work in Vietnam in a relatively small city, we worked with local partners to design and build traps made of relatively inexpensive, readily available materials as a way to ensure replicability of the project.

Another advantage of the design is that the traps are emptied manually by local workers, creating local jobs within the community. When I visited Nam Dinh, it was encouraging to observe the pride that the workers took in contributing to a healthier environment for their communities.

Overall, one of the major takeaways from the SPLASH project is how important it is to involve the community and local authorities at multiple levels in environmental work. This cooperation leads to more sustainable outcomes in the long term and healthier rivers and ocean as a result. We look forward to learning more from the survey results to understand how the community’s attitudes regarding plastic pollution have shifted.

Learn more about Ocean Conservancy and their work:

Learn more about MCD and their work: