The initial trial phase of The Ocean Cleanup’s operation in Kingston Harbour is complete, and the second phase has begun with new Interceptor deployments across the city.

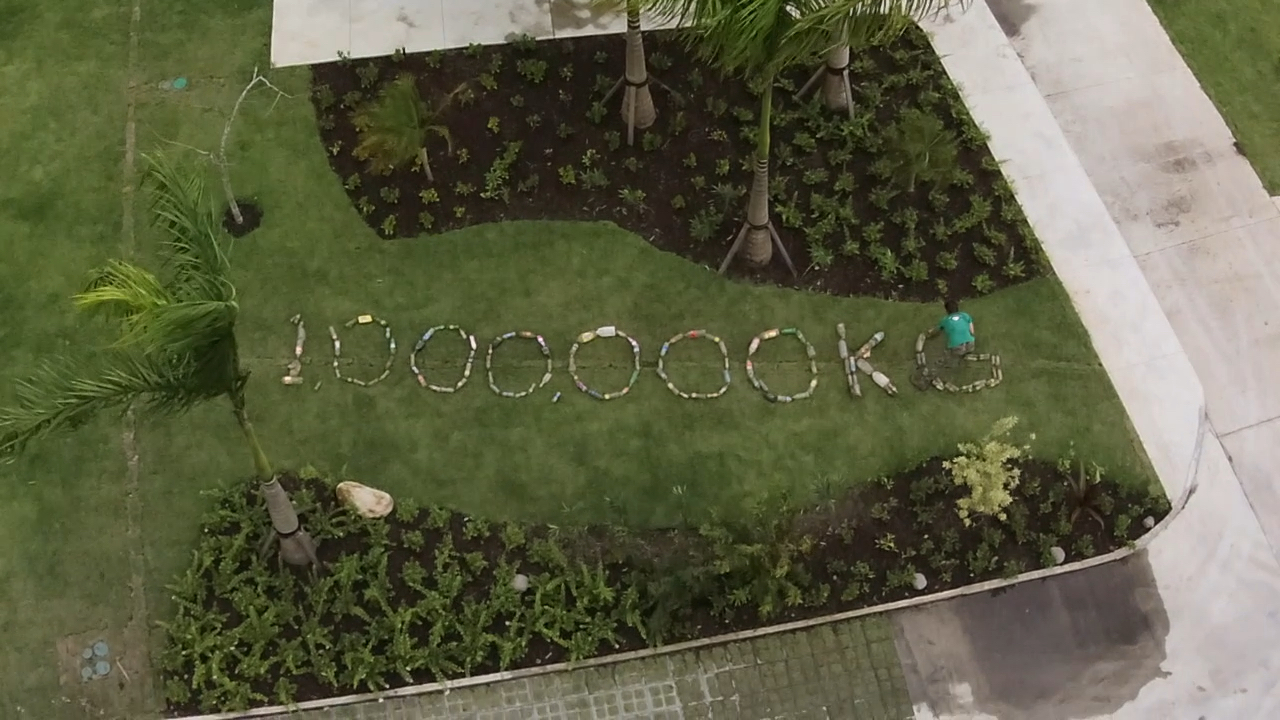

The impact of our early deployments has been significant, with over 130,000 kilograms (over 285,000 lbs) of trash removed from Kington’s gullies. From the initial three Interceptors, there are now five operating throughout Kingston, with the intention of expanding to seven by the end of 2023.

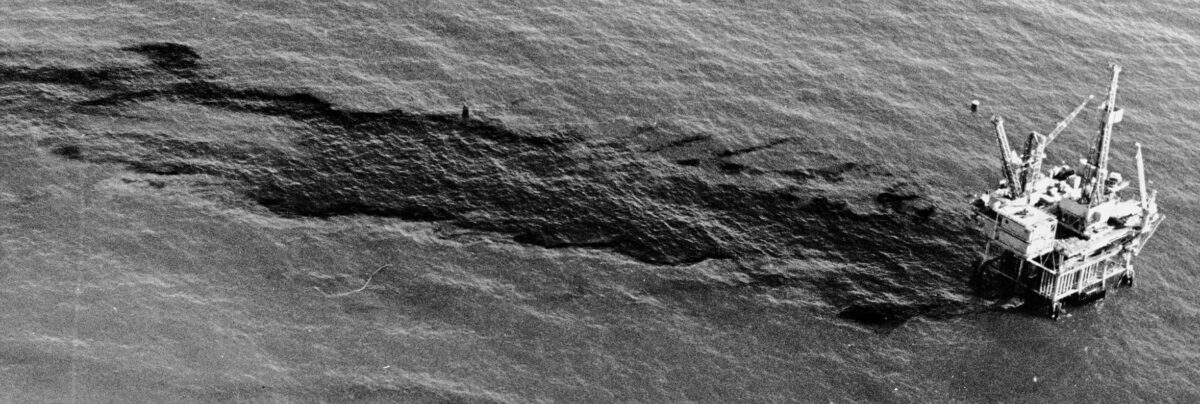

The Ocean Cleanup teamed up with Clean Harbours of Jamaica and the GraceKennedy Foundation in 2021 with the aim of reducing the pollution devastating the gullies and waterways for local residents and leaking plastic waste into the Caribbean Sea – contributing to the plastic pollution crisis in our oceans. The project aims to capture trash in eleven gullies around the city, beginning with the deployment of Interceptors 008, 009 and 010 to capture waste in three trial locations: Rae Town Gully, Kingston Pen Gully, and Barnes Gully.

These deployments have been a learning process for everyone involved, and we’ve analyzed our results while engaging with Kingston authorities and the local community to assess our impact and ensure that the benefits of our anti-pollution efforts are shared by everyone.

LEARNINGS

Following the success of our first three Interceptor deployments, there are several key learnings we have taken forward.

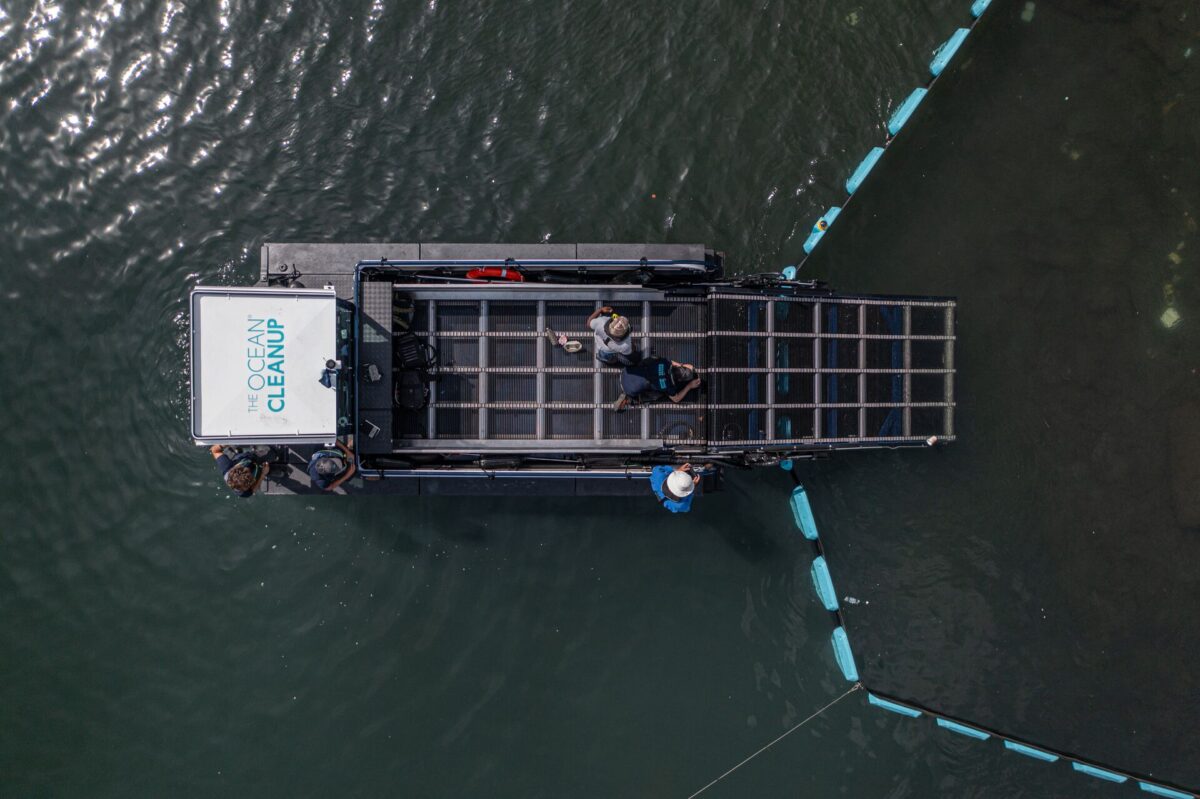

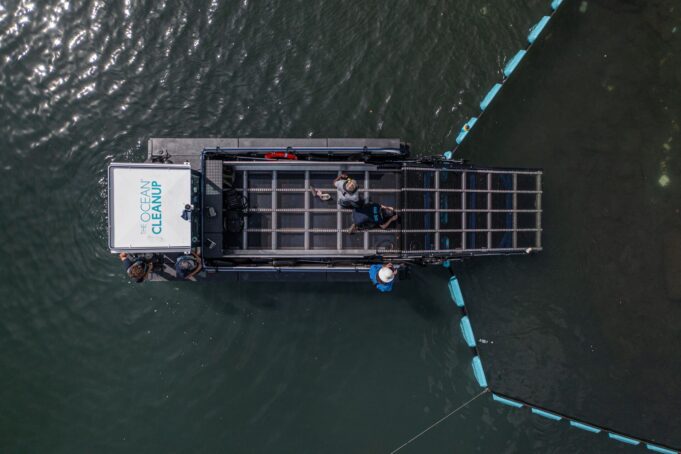

First, we must identify ways to optimize the Interceptor Barrier and Interceptor Tender to improve the capacity and efficiency of our debris harvesting. Waves formed in the wake of passing vessels can disrupt the functioning of the Interceptor Barrier, and the blustery winds around Kingston Harbour mean the captured waste often gathers far from the shore, making extraction more difficult and time-consuming than predicted. To address this latter problem we are currently developing ‘non-return barriers’ and we are expanding our extraction and offloading capacity by adding a support vessel to supplement the Interceptor Tender.

Our operational partners Clean Harbours of Jamaica are also continuing to examine other operational ways to make waste extraction and management more efficient.

Second, we are now looking for new solutions to capture trash in the next three gullies on our list, where our current Interceptors may not be suitable. Coastal waters are difficult for the Interceptor Tender to access, while shallow waters present a challenge for the Interceptor Barrier, so we are looking to develop new solutions (potentially in collaboration with third party technology providers) to ensure our Interceptors are fit to tackle trash throughout the rest of Kingston Harbour. Other design learnings have already been implemented – for example removing a semi-permeable screen on the Interceptor Barrier which was susceptible to excess marine growth.

We have already introduced the latest addition to the Interceptor family, the Interceptor Guard – our newest technological solution designed to better withstand the environmental conditions of the harbour.

Thirdly, we have learned more about the composition of the trash in Kingston’s waterways: what this trash is, and where it comes from. A significant amount is plastic, often from consumer products and single-use items. Understanding the nature of this problem is essential to solving it, and the data gathered through our extensive river monitoring and the thorough sorting process conducted at the offloading site are essential in evaluating the effectiveness of other anti-pollution measures further upstream: if we start to notice that there is less trash than there used to be flowing into the gullies, we will know that fundamental change is occurring in Kingston.

While we have seen that waste levels fluctuate with water levels according to the wet and dry seasons in Jamaica (information we can use to predict periods of high quantities of waste and increase capacity accordingly), our project has demonstrated the scale of the pollution problem in these gullies all year round, and the huge benefits that can come from tackling it.

A final takeaway is the strength of support we have received from Kingston’s residents and authorities during our operations. A priority throughout this project has been community engagement, which has been fostered through frequent school visits to the offloading site, where all the captured waste from all the Interceptors is brought for sorting and processing.

The offloading site itself is another example of how this collaboration is extending out of the water and onto the shore. Formerly an abandoned dumping ground, the site now operates as both a place of work and education, featuring offices, murals, and even a conference room as well as the required trash sorting equipment and personnel. Now the site is safe and operational, it is frequently visited by touring schoolchildren from across Jamaica – spreading awareness of plastic pollution, giving insights into possible actions and solutions, and allowing these young people to take this information home with them and act as drivers of change.

The employees at this site, too, share in the benefits of this project. Full safety certification and training is available, while all workers – many from lower socio-economic backgrounds – are supported in attempting to gain qualifications and training while in work. One example saw employees trained to better recognize and categorize plastic during sorting. As well as enhancing the performance and abilities of the staff, this also had the effect of making our sorting more efficient; a full-circle benefit, with local people at the center.

SCALING UP: INTERCEPTOR CITY

With five Interceptors deployed and two more scheduled for this year, our project to transform Kingston Harbour continues. The Ocean Cleanup, GraceKennedy Foundation, and Clean Harbours of Jamaica are committed to tackling plastic pollution in Jamaica, and we are optimistic about the next phase.

The next deployment will be in Mountain View Gully and will feature a new concept combining components of various systems to form a new Interceptor. After this, we will continue to expand to other gullies, with a special focus on possibly the most challenging of all: Sandy Gully, which will require a more specialized approach. All this while continuing to build and maintain relationships with local residents, fishing communities, businesses, school and officials, aiming to keep us all pulling in the same direction as we work together to transform Kingston Harbour.