This post is also available in: Español (Spanish)

Last year, because of pandemic consequences and the “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) effect, we came to the forced conclusion that we would need to change the project site from the Matias Hernandez River to the Juan Diaz River, both in Panama City. We started this project in 2017 since we were tired and frustrated from witnessing tons of garbage drift down daily to the mangroves and ocean. We started working in the Matías Hernández River because it is our backyard.

At that time, we began with constant and straightforward mangrove cleanups, as well as researching ways we could prevent this garbage from reaching the oceans by collecting it while still in the river. With many data unknowns, it took us over two years to define a system, location, operation plan, and have authorities and other key stakeholders aligned to permit the installation of a floating barrier as a pilot.

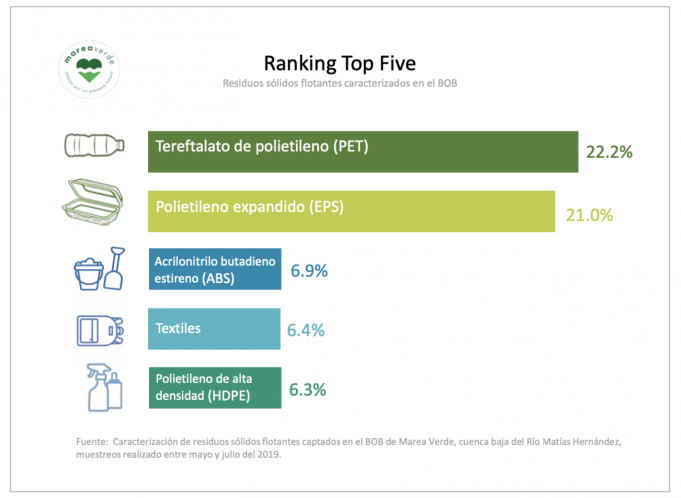

As a pioneer in Panama, our barrier B.o.B (for “Barrera o Basura”, in Spanish; “Barrier or Trash” in English) got a lot of press attention, particularly after big storms when most garbage accumulated in the barrier. From the beginning, we were interested in having this pilot serve as a tool for data generation, best practices, and inspiration for others to replicate it in as many rivers as possible. We invested a lot of effort in maximizing the barrier’s efficiency in trapping garbage, improving its retention capacity, and removal time from the river. We kept statistics of garbage weight and volume retrieved from the river, and performed several characterization exercises, enabling us to generate interesting information on the type of garbage that flows in the river, a first for a Panama river.

Since we were already working in the Matías Hernández River, it was logical for us to propose this site to the Benioff Ocean Initiative call for proposals in 2019. Before we could begin executing this grant, the COVID pandemic and the start of the 2020 rainy season hit us, and the garbage accumulation combined with mobilization restrictions caused unforeseen inconveniences to our neighbors. Despite our efforts to mitigate these inconveniences and gain support for the project, there was no tolerance for our pilot’s presence on that site. This is a common phenomenon – everyone agrees the environment’s protection is important, but not all are willing to sacrifice comfort, or put time and work to contribute to this common cause.

We were wrong to assume our neighbors shared our goals for a garbage-free wetland and ocean (their larger backyard), particularly as this is a project with no financial burden on them. Keeping true to our organization’s mission and goals, our Board of Directors was not willing to insist on implementing a positive project, despite the legality of our presence, in a place where we would be in constant conflict with the community. We, therefore, removed our floating barrier on July 29, 2020.

We applied our newly gained knowledge in the search, design, and characteristics of a new project site. We were able to identify three new potential sites for our project. The place needed to have certain characteristics, such as proximity and access to an urban and polluted river, proximity and access to road, access to electric/ wifi grid, and very importantly: buy-in and support from neighbors in addition to authorities and other stakeholders. Two of the sites are in the originally proposed Matías Hernández watershed, and the third is in a different but contiguous watershed, the Juan Díaz river.

Early this year, after much debate of the pros and cons of each site, analyzing different aspects, including political, social, and economic aspects, our Board of Directors agreed to move the project to the Juan Díaz River.

The Juan Díaz watershed is one of the largest watersheds in Panama City. It is densely populated in its mid and low watershed portions, but maintains important forest cover in the upper watershed, in the river origins, and it ends in an important Ramsar site and Bay of Panama Wildlife Refuge. This protected wetland spans over 85,664 km2, and comprises, among other features, lagoons, grasslands, floodplain forests, and mangroves. It is home to many fauna and flora species, over 295 plant species, 25 mollusks and crustaceans, 200 birds, 74 fish, and 50 mammals. Over 27 species of fiddler crabs have been described for this protected area, more than anywhere else in the world. Globally threatened species that live in this wetland include the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus), spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi), giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), tapir (Tapirus bairdii), and the tea mangrove (Pelliciera rhizophorae)1.

These last six months have been spent gathering information, commissioning different studies (soil, topography, hydrology, hydraulic, environmental impact assessments) needed for permits, redesigning our trash-trapping device and architectural plans, and communicating about the project to different stakeholders, authorities, communities, neighbors, private sector and non-profit allies, etc.

We are confident that “things happen for a reason” and that this setback will allow us to execute a more robust project, with better allies, better communication strategies, and the needed social license to operate effectively.